The Scots in Monfalcone, a Forgotten Story

The city of Monfalcone has been in the national and international headlines in recent months due to the presence of a crowded Bengali community crucial for the construction of large cruise ships by Fincantieri in the city’s shipyard in the Isontine region.

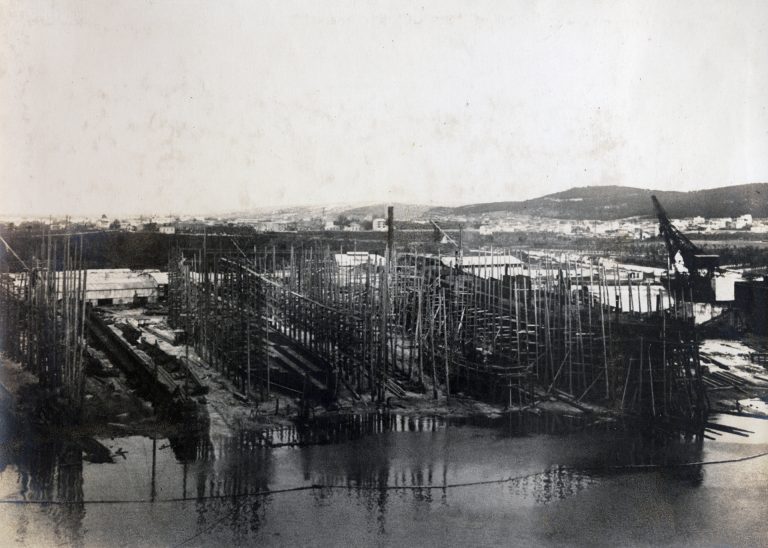

Monfalcone prima della guerra

Monfalcone

This phenomenon began around 2000, progressively altering the city’s social fabric. However, not everyone is aware that migration for work in the shipyard started immediately after the foundation of the large factory by the Cosulich family, owners of the Austrian Navigation Union. This article will delve into this forgotten story, focusing on a community of Scottish workers rediscovered in the book “In Cantiere,” published in 1988 on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the famous shipyard’s founding, which now produces passenger ships that are a pride of the Made in Italy industry.

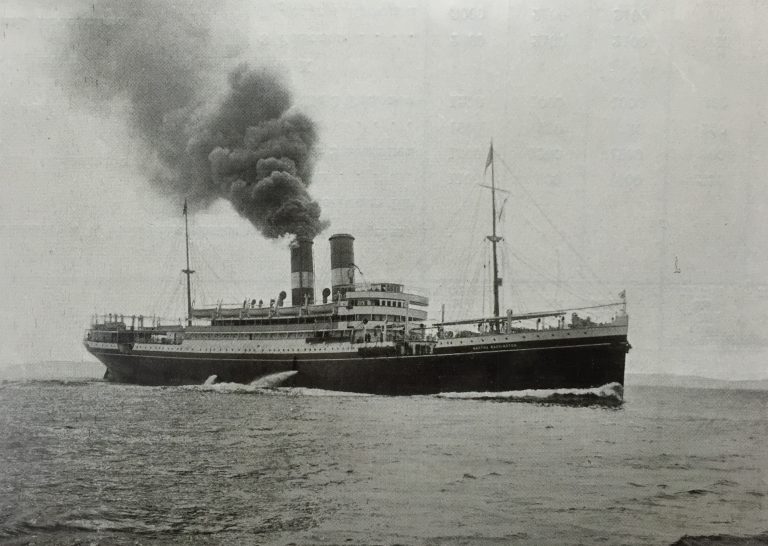

The first significant new construction ordered by the Austrian Navigation Union was the transatlantic ship Martha Washington, commissioned from the Scottish shipyards Russel & Co in Port Glasgow. With 8,145 gross tons, it was launched on December 7, 1907, and set sail for its maiden voyage on May 22, 1908. This allowed the Cosulich family to experience the leadership of Britain’s shipbuilding industry at that time.

ss Martha Washington

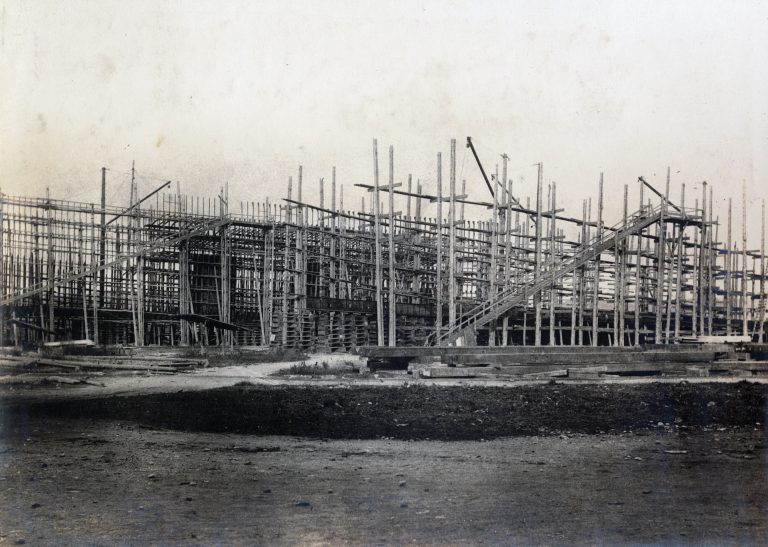

Callisto Cosulich decided to entrust the Technical Direction of the newborn Triestino Shipyard to the Scottish engineer James Stewart, already employed by the Austrian Navigation Union as a technical inspector. Stewart brought around 200 skilled workers from Britain to Monfalcone (then Austrian) for various ironwork categories, while for woodworking, he turned to master shipwrights from Lussinian and Istrian regions. These workers, along with the ship carpentry school opened within the shipyard in 1911, trained many young people from the Monfalcone area. For heavier manual labor in the Naval Workshop, and for the categories of riveters and caulkers, preference was given to people from the Karst region (Doberdò area) or to farmers brought in from the interior of Istria.

In April 1908, there were 35 “Britons,” but soon another 150 arrived, while unskilled local workers were hired. The reason for hiring subjects of His Majesty is easily explained. The iron carpenters from the San Marco Shipyard and the Lloyd Arsenal (who could easily be attracted to Monfalcone with higher salaries) were used to working in a reality where business profits were assured by the already consolidated relationship with a state client (as was the case with San Marco, which had been working mainly for the I.R. Kriegsmarine for a decade) or by the heavily supported state (as was the case for the Lloyd Arsenal).

Swift and timely deliveries were certainly less important at San Marco than the significance these factors took on in Monfalcone, where the Cosulich family had to just secure their market share. Moreover, at San Marco, in military constructions (especially for battleships), the priority was the need to create an accurate and perfectly finished product. This had accustomed workers to acquire a “professionalism” that was both a taste for well-done work and a tool of power to resist any demands for increased pace and acceleration of the production cycle. Therefore, for the Cosulich family, given the opposite needs they had, it was better to rely on professionals trained in shipyards in a country where the naval industry had been operating with a production and market-oriented perspective for decades (which the entrepreneurs originally from Lussino knew very well).

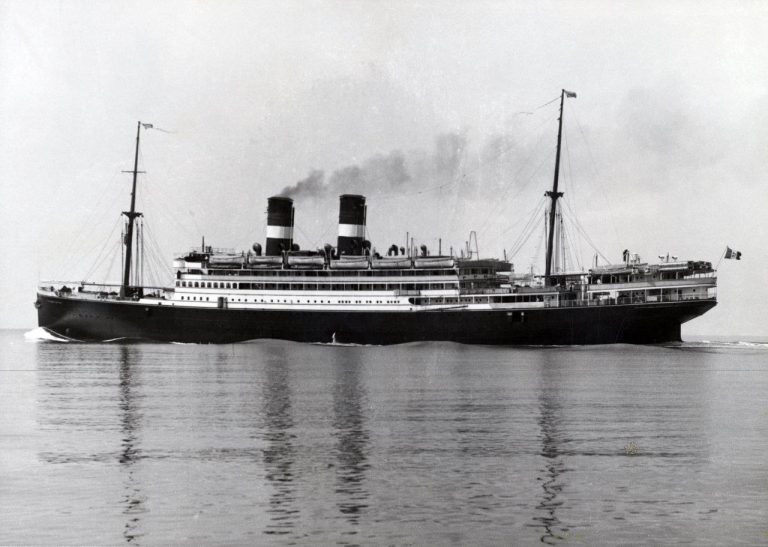

Kaiser Franz Joseph I, Unione Austriaca di Navigazione (1912), 12.567 TSL

Monfalcone dopo guerra

In this sense, thanks to the techniques and work habits brought by the British workers, Monfalcone introduced more expeditious procedures (sometimes the innovations were very trivial, like using chalk instead of pencils for the surveys with the squares, and yet even these were used to save time). It was rumored, whether true or legend, that the foreman of the San Marco in Trieste spent some time in Monfalcone “disguised” as a simple worker, to “steal” some of the innovations brought from Britain.

However, there was also a downside to hiring these workers: they cost the company a lot (they earned between 12 and 15 Crowns per day, while a local professional earned a maximum of 8-10 Crowns); they demanded respect for British working hours, causing discontent among other workers (and this led to the first two strikes in 1908); they certainly did not represent a good “model” for disciplining the behavior of young people coming from the countryside (“they earned 12 Crowns a day and drank 16,” was the joke passed down in the oral memory of the shipyard workers). Therefore, also considering the crisis that the company went through in 1909-10, their contracts were not renewed, and, except for a few dozen, from 1910-11 they were replaced by skilled workers from Muggia and Trieste.

Monfalcone dopo guerra

The few survivors left Monfalcone at the outbreak of World War I when they officially became “enemies” of the Empire. Instead, just on the eve of the conflict, the Technical Director, the Scotsman James Stewart, although he had already reached a preliminary agreement to renew his contract by emphasizing Austrian citizenship, left the CNT at the end of May 1914 to take up the position of director of the Ottoman state shipyards. Thus ended the experience of the British workers in Monfalcone, leaving behind the imprint of their workers’ villages, which would be taken up again after the war to build the Panzano neighborhood.

More generally, the impact of immigration in the Monfalcone area after the founding of the CNT was strong from the outset, as evidenced by the demographic data of the territory. Between the beginning of the century and the outbreak of the Great War, Monfalcone’s population increased from 4,500 to 12,000 people; an increase due to the establishment of new industries like the CNT, which employed around 3,400 workers in 1914. Obviously, the territory could not provide the necessary workforce, so the Bisiacaria immediately became an attraction for those looking for work.

Crown Princess 1990

In 1919, it was the turn of the migration of the Gallipoli people, still witnessed today by the twinning of Monfalcone with the city of Gallipoli. After the Second World War, it was the turn of the Istrian, Rijeka, and Dalmatian exiles who took the place of the “red” workers who had emigrated to Yugoslavia. Finally, starting from 1989, a large community from Southern Italy arrived in the city to outfit the first new-generation cruise ship, the first Crown Princess. With the boom of the white ships, Albanians, Romanians, Serbs, and finally, the most numerous, Bengalis also came to the city.

Stay tuned for more news, updates, and reviews on the world of cruises on Cruising Journal.