Cruise ships toward zero impact in 2050

In recent years, there has been no shortage of controversy over pollution from cruise ships. This is because large passenger ships are always under the media magnifying glass, even though the cruise industry is the most virtuous sector of shipping in terms of environmental protection. Other types of vessels are the ones that pollute the most, but it’s always easier to pick on “big ships” even though people often don’t know what they’re talking about, so let’s get some clarity.

The first myth to dispel is the one that the bigger the ship the more it pollutes. Nothing could be more wrong! In fact, the environmental impact of a passenger vessel depends on the technology with which it is designed, so newer ships pollute less even though they are on average larger (gigantism is a phenomenon that has become more pronounced in the last two decades) than older ones. This is because they employ state-of-the-art environmental protection technologies derived from multimillion-dollar investments by shipbuilders and shipowners.

Msc World America

Europa Promenade MSC World

Recall that the cruise industry has set a goal of achieving zero impact (carbon neutral) by 2050. We will now see what the steps are to achieve this virtuous goal. But first we need to start from today’s situation.

Remember that the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has set a target to reduce sulfur emissions from 3.5 percent to 0.5 percent by 2020, so there has been a rush to comply with these new regulations in the past few years. It must be remembered that there are different types of marine fuels that depending on their state of refining have higher or lower sulfur content. So here they are from the more expensive and refined one and the cheaper and heavier one:

1) MGO (Marine Gas Oil): classified as a typical light naphtha, it is a medium distillate with a density of about 850kg/m and is used in medium-fast and fast 4-stroke engines.

2) MDO (Marine Diesel Oil): still definable as light naphtha, with a density of about 870kg/m, is produced by blending diesel fuel with small amounts of HFO and is always used in 4-stroke diesels.

3) IFO (Intermediate Fuel Oil): obtained by mixing HFO with various amounts of MGO until the desired viscosity is obtained, it is used in large marine engines both 2- and 4-stroke; it is indicated by the abbreviation IFO followed by a number expressing its density at 50°C in centistokes (e.g., IFO180 or IFO380).

4) MFO (Medium Fuel Oil): another mixture between MGO and HFO, but with smaller amounts of gas oil than IFO.

5) HFO (Heavy Fuel Oil): low-distilled heavy naphtha characterized by its viscosity.

Silversea

Ships cannot always burn MGO because the latter is very expensive and so to save money, they usually use HFO in navigation especially in seas not classified as ECA (Emission Control Area). So, do they pollute a lot? No, because they use flue gas cleaning systems, so-called “scrubbers.” Now without going into the details of how they work, we can say that they are “scrubbers” of engine exhaust gases. They usually employ water mist, and the result of this operation can be seen when the funnel of a ship emits a thick white smoke that is nothing but water vapor. Scrubbers can be of two types, open loop and close loop. In the former, the polluting residues from the “scrubber” are discharged into the sea after being inerted; in the latter, these are stored on board and then discharged into port to be taken to authorized disposal sites.

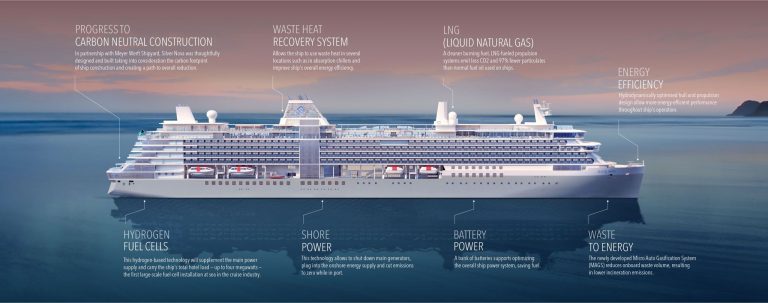

However, the scrubber is not needed if we are talking about a ship with dual fuel propulsion, that is, equipped with engines capable of consuming both traditional bunker and the much “greener” liquefied natural gas (LNG). The latter we say is the most environmentally friendly current technology available for large electric utilities such as ships of 50,000 gross tons and up. It is probably a “gateway” fuel that will ferry the cruise industry toward climate neutrality. The use of LNG instead of marine diesel fuel offers numerous benefits in terms of reducing atmospheric emissions, here are some of them: absence of sulfur dioxide (SOx) emissions, about 25 percent reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, about 85 percent reduction in nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions, about 95 percent reduction in particulate matter (PM) emissions.

Costa Toscana

Costa Toscana Bar Sport

Costa Crociere

In December 2018, AIDAnova (by AIDA Kreuzfahrten, a German brand of the Costa Group within Carnival Corporation & Plc.), the first large ship equipped with dual fuel engines, entered service. Electric generation on this 183,858 gross tonnage vessel is provided by four Caterpillar/MAK dual fuel engines for an installed power of 61.76 MW. Only in 2009 did Costa Cruises take delivery of Costa Pacifica, a much smaller ship (114,288 dwt) but which had an installed power of 75.6 MW. This figure shows us how far technology applied to cruise ships has come in the field of energy conservation with direct consequences in environmental protection.

Aida_Nova

Aida Nova

Aida Nova

The future will probably be hydrogen fuel cell propulsion, which, however, is still in the experimental stage at the moment and therefore available for still limited electric utilities. In Explora Journeys‘ plans for example, there is a desire to study with Fincantieri this technology in order to be able to guarantee electric generation with a stationary ship in port of more than 10 MW, and this would allow diesel engines to be turned off, avoiding emissions near population centers.

Explora Journeys

But one way to stop diesels in port is already there, we are talking about cold ironing. With the electrification of the docks, ships can be powered by the electric grid (large powers are needed, of course). All modern ships are already set up for cold ironing, too bad that port infrastructure has not kept pace with this technology, which has been available for about fifteen years. Ports with electrified docks are few in the world, and furthermore there are detractors to this solution as well who assert that it is just a shift of pollution to where energy is produced if fossil sources such as coal are used.

Another way to have zero impact in port are batteries that are recharged while sailing and then used at the dock to power the ship. A virtuous example in this case may be that of Grimaldi Lines’ cruise-ferries Cruise Roma and Cruise Barcelona, which on the occasion of their extension in the Fincantieri shipyard in Palermo received the installation of lithium batteries that allowed the prestigious slogan “zero emission in port” to be painted on their sides. The current problem is the size of these installations needed for large electric utilities such as those on mass market cruise ships. Improved batteries could lead to the order of the first ship with such electric generation in 2030 with entry into service in 2035.

MSC Seascape

Msc Seascape Signature Casino

In short, the industry is really making big investments to weigh as little as possible on the environment: LED lights, highly hydrodynamic hulls, antifouling paints that reduce resistance to motion, and air sulbrification systems, on the other hand, are already technologies used in series on all ships. The future is already here, and the cruise ship should instead be a virtuous example of environmental friendliness.

Don’t miss updates, news and tips about the world of Cruising on Cruising Journal with photos, videos and cruises on offer.